Functors and Applicatives

I recently gave a talk at Hartford JS on Functors and Applicatives in JavaScript. This subject assumes familiarity with currying and function composition. You can also look over the original slide deck.

Q: When is a function not a function?

A: When it is a method.

We’re talking here about functions and not methods. For the purposes of this discussion, a function:

- Maps some input

ato some outputb; - For any input

a, there is only one outputb(although anybmay be mapped to by more than onea); - Does not mutate any state, encapsulated or otherwise, nor does it produce side effects.

Contrast this with a method:

- May return something, or not;

- May return a different

bfor an inputa; - May mutate state somewhere. May produce side effects.

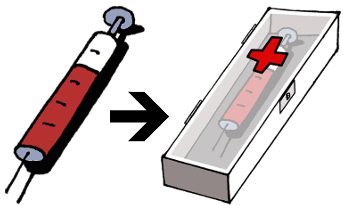

Let’s look at a simple example function. You want to take your cat to the vet to get a shot for it.

Here we have a simple function from Cat to Cat. We input a cat a on the left,

and we get out an immunized cat b on the right.

It’s important to note that we should not mutate the input cat. What should happen

instead is we input cat a on the left, and get out a brand new cat that is immunized.

Then cat a can be made available for garbage collection.

Of course, there’s no guarantee that people coming into the vet’s office have a cat–or any pet at all,

for that matter. If someone brings a null where we are expecting a Cat, then our nice function from

Cat to Cat doesn’t work so well:

We could have the vet ask everything that comes by if it is null or not. But that is not his job, really. His

job is giving shots to pets. I don’t want all of my functions littered with null checks. Surely, there must be

some way to keep my functions clean and simple, yet make them null-safe as well?

The answer is “Maybe”–more specifically, the “Maybe Functor”.

Note that when you are composing functions, all the functions in the composition have to

fulfill their contracts. If somebody returns a null in there, the whole daisy chain is borked. Consider:

// capitalize :: String -> String

var capitalize = R.compose(

R.toUpperCase, // String -> String

R.prop('textContent'), // Object -> String

R.bind(document.getElementById, document) // String -> DOMElement

);

What happens if the call to getElementById doesn’t find anything? You get a null back. Then

that null gets fed to R.prop, and R.prop will fail.

To get around this problem, we can use a Functor.

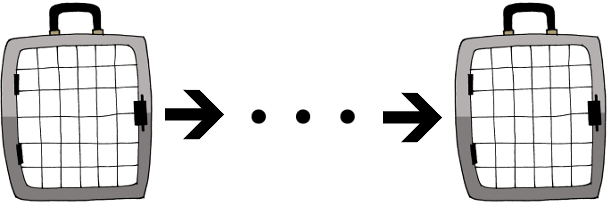

A Functor is an object that can be mapped over. By “map” I mean that we can use the same function from Cat to Cat even though the Cat is now inside a container. Note that in the example above, The cat is in the kitty carrier, but we we are still using the same immunization function.

This is a big deal, because it allows us keep the null-checking separate from the internal logic of

the function. Now if we get an empty container for input, then there is no reason to even try to apply the

function to its content. We simply get an empty container back.

This example is essentially the “Maybe” functor. “Maybe” let’s you wrap up a function from a to b

so that you can apply it to the contents of the Maybe. Take a look at how we have implemented Maybe in Ramda Fantasy.

You can see that Maybe is a sum type; it is a Just of some value, or it is Nothing.

You can use the direct your composition into the proper channel with something like:

function fromNullable(x) {

return x == null ? Maybe.Nothing : Maybe.Just(x);

}

Now let’s go back to the capitalize example. We can rewrite that to make use of the Maybe functor:

// capitalize :: String -> Maybe String

var capitalize = R.compose(

R.map(R.toUpperCase), // Maybe String -> Maybe String

R.map(R.prop('textContent')), // Maybe Object -> Maybe String

fromNullable, // Object -> Maybe Object

R.bind(document.getElementById, document) // String -> DOMElement

);

Now this function is guaranteed to output something–Maybe. If the call to getElementById fails,

we’ll wind up with a Maybe null at the end; otherwise we’ll have a Maybe String. We didn’t have

to guard inside our functions, so that is nice. Instead, we have wrapped up the value we are composing

over inside this container. So we can only access the value by mapping over the container.

(Well, actually, since this is JavaScript, and value is sitting there as a public property on Maybe,

you could just query it. But then you are right back where you started, needing to test for null.)

The Maybe functor only gives us one bit of information: Did we hit a null somewhere along the way or not?

There are other functors that can wrap up more info. The Either functor is either a Left or a Right;

In the Left you can put an error message (or a function, or whatever). If it is a Right, then everything

ran fine.

Promises can also be looked at as functors. Consider:

R.map(function(a) { return a + 1; }, Promise(2)); //=> Promise(3)

There are many, many more ways to skin this cat: Validation, IO, Reader, Writer, State, Future … and of course Array.

R.map(function(a) { return a + 1; }, [10, 20 ,30]); //=> [11, 21, 31]

Arrays are Functors. After all, it’s a container you can map over. Arrays are a bit trickier, though, since they are intertwined with the notion of iteration.

No reason to stop here, though. We can wrap up the object we’re mapping over in a Functor. We can also wrap up the function we want to apply inside a container:

Once again, it’s the same function from Cat to Cat, but now both function and data are wrapped in containers. The good folks

from Fantasy Land call an object that can handle this

situation an “Apply”, and the function you

use to apply a wrapped function to a wrapped value is ap. For Maybe, that could look like this:

Maybe.prototype.ap = function(vs) {

return (typeof this.value !== 'function') ? new Maybe(null) : vs.map(this.value);

};

The implementation of ap for Array is a bit more complicated, of course, because of iteration:

R.ap = curry(function(fns, vs) {

return foldl(function(acc, fn) {

return concat(acc, map(fn, vs));

}, [], fns);

});

Maybe you are asking yourself, “How do you get into a situation where you have a function inside a container?”

I covered such a situation recently. That article also covers the

ability to create an Applicative, by wrapping up an arbitrary object inside a container via of:

Here’s how we implemented of for Maybe:

Maybe.of = function(x) {

return new Maybe.Just(x);

};

And the implementation for Array is trivial:

R.of = function(x) { return [x]; };

Please read my article on Applicatives for a real-world example of these concepts in action. Gleb Bahmutov has also written a good article on using Applicative Functors with Promises that goes more in depth in the code than this article did. And I also should mention the excellent illustrated article Functors, Applicatives, And Monads In Pictures, by Aditya Y. Bhargava.

Thanks to J. C. Phillipps for the illustrations. No animals were harmed in the writing of this blog post.

26 October 2014